This is Boudhanath, the neighborhood where I am staying. The photo is borrowed from the internet, because it’s a drone shot. I am three minutes’ walk from the stupa in the center.

This is how the stupa looked when I was walking home last night.

Last year I had the good fortune of staying at a hotel called Hotel Lotus Gems. It’s owned by a local dharma family with deep roots in Dolpo, a region of northern Nepal, close to the Tibet/China border. The proceeds from this hotel go to the humanitarian projects of the family’s Tibetan Dharma teacher.

Last year I was one of a tiny handful of guests at the hotel so there was lots of time to get to know staff. One of the front desk staff is a young man named Karma. He hails from Dolpo, as many of the staff here do. One day, I was admiring a painting on the wall and I asked Karma about it. He said, “It’s a painting of life in Dolpo. My father, Tenzin Norbu painted it.”

A view of Dolpo in Nepal:

Yes, Phoksindu Lake is actually this color. I have seen it:

This could be us in Dolpo:

This year the hotel is full of guests. This morning at breakfast, I can hear French and Chinese guests enjoying morning conversations. But Karma is still here, and in between large groups, we still manage to connect and I am learning more about his life and family. He’s a little shy, so these conversations take time, but I can tell he enjoys sharing about Dolpo, his family and his life. The longer the conversation goes, the faster he talks and the straighter he stands.

Yesterday, he carefully drew a map of how I could get to a place called Caravan Cafe. It’s location included a lot of hints like, “There is a sign that says Dolpo Gallery, which is actually not there, any more…”

So after breakfast I took the small scrap of paper that was the map and went down the stone paved road near the hotel and rounded the corner onto the muddy lane that leads to the stupa. It took a bit of wandering, but finally I found it:

It appears that Cafe Caravan used to be Karma’s father’s gallery. Now his father has moved back to Dolpo and works there again as an artist and leader of some humanitarian projects like schools.

The cafe name is a reference to the French movie Caravan. Here are a few clips from the film on YouTube. It was nominated for an Oscar for best foreign film the year it came out.

Karma’s father, Tenzin Norbu, was a technical advisor for the film. Tenzin was trained in thangka painting and is in a family lineage of 400 years of thangka (Buddhist scroll painting) artists. But at some point in his life, he met a Frenchman who took him to France and together they visited many museums, gallery’s and other cultural scenes.

It occured to Tenzin that he could step outside the thangka tradition of painting in a very carefully prescribed way of Dharma story telling to create paintings in his own style. And after the long visit in France, he came to feel that his own culture was a kind of art, which could be expressed in the thangka style and so he began to paint everyday life in Dolpo—in the thangka brush style.

Here is Tenzin as a young man, working on a painting:

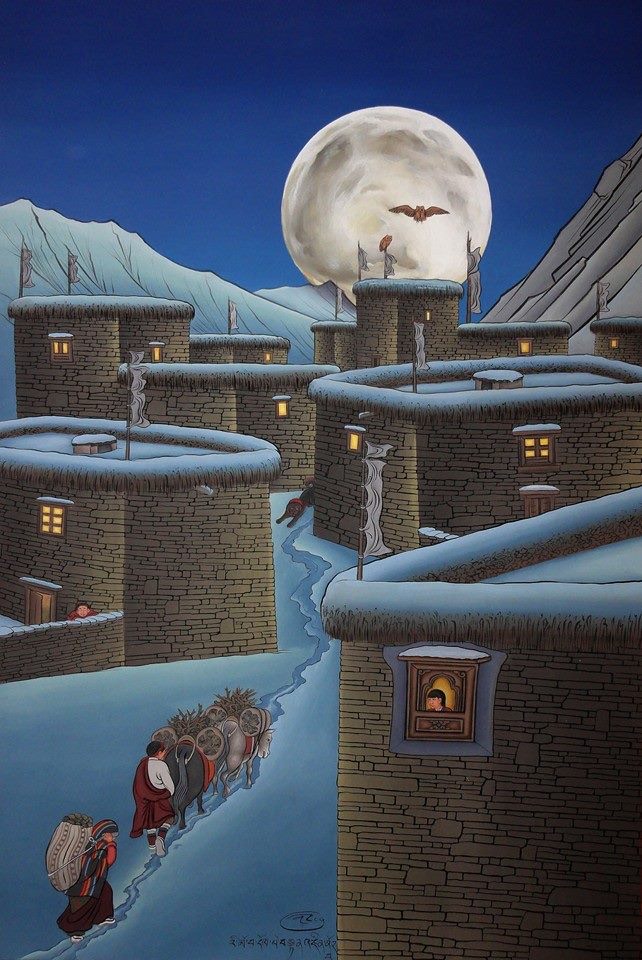

Here is Tenzin’s painting of a snowy night in Dolpo:

Dolpo can be visited today so that one can see these things for oneself. Tenzin has illustrated children’s books, which you can find online.

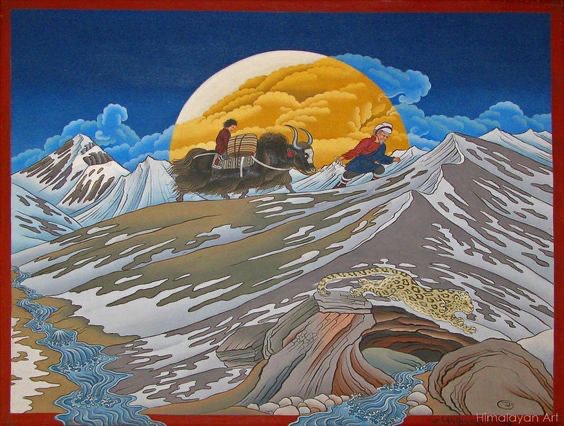

The Dolpo people live a Tibetan lifestyle. They have many kinds of herd animals, including yaks. Yaks are especially revered by the Dolpo community becuase they are the most hardy of the herd animals. Not only can they carry heavy loads, but they give milk, which can be made into butter and yogurt. The movie Caravan shows the relationship between the Dolpo people and their yaks.

Last night I was having tea at the Caravan Cafe with a young woman named Sonam Lhamo that I met last year at the gallery where I bought Dekeling’s Green Tara and Chenrezig thangkas. She is college age and hails from a village in the far, far west of Nepal, called Limi. (Limi, she told me, means the people near the river’s border.) Their village is right against the Chinese border.

Sonam is smart and remarkably confident. In her village, the environmental conditions in winter are quite harsh, so even children have to work hard. She told me that their yaks liked to be out in the out-of-doors all winter, so they let them wander. Then in spring and they would go collect their animals and get ready for their time together. Sonam told me a yak in deep snow can survive for up to a month without food or water, unlike the goats and sheep which would die if not close to the village.

This is a yak:

And this is a yak:

And this is a yak with clothes made by people who value their yak-friend:

This is why you see yaks in so many of Tenzin’s paintings:

Sonam Lhamo and I were looking at dozens of prints of his paintings (they make canvas prints here). She got teary-eyed seeing the very life she lived as a child treated as precious art. For two hours she kept pointing out tiny details my eye might have missed. She said these details were all accurate and tell many important stories which are quickly disappearing. Looking at one kind of striped wool bag for storage of grain and salt, she explained to me how these bags were made and how, as a child, she had to twist yak wool threads to make ties for the bags.

Here is Tenzin Norbu working on a large-scale painting which is stretched in the traditional style used for thangka, paintings as well. He works in stone color—a very, very laborious process that involves grinding the stone to make pigment:

Some of Tenzin’s paintings are not about village life. (Or maybe they actually are, now that I think about it.) Such as this one, a traditional mandala, but it’s melting. (At the bottom is an ice cream cone, immortalized.) I don’t know what this painting is about—maybe climate change? Or the change of village culture (melting away?)

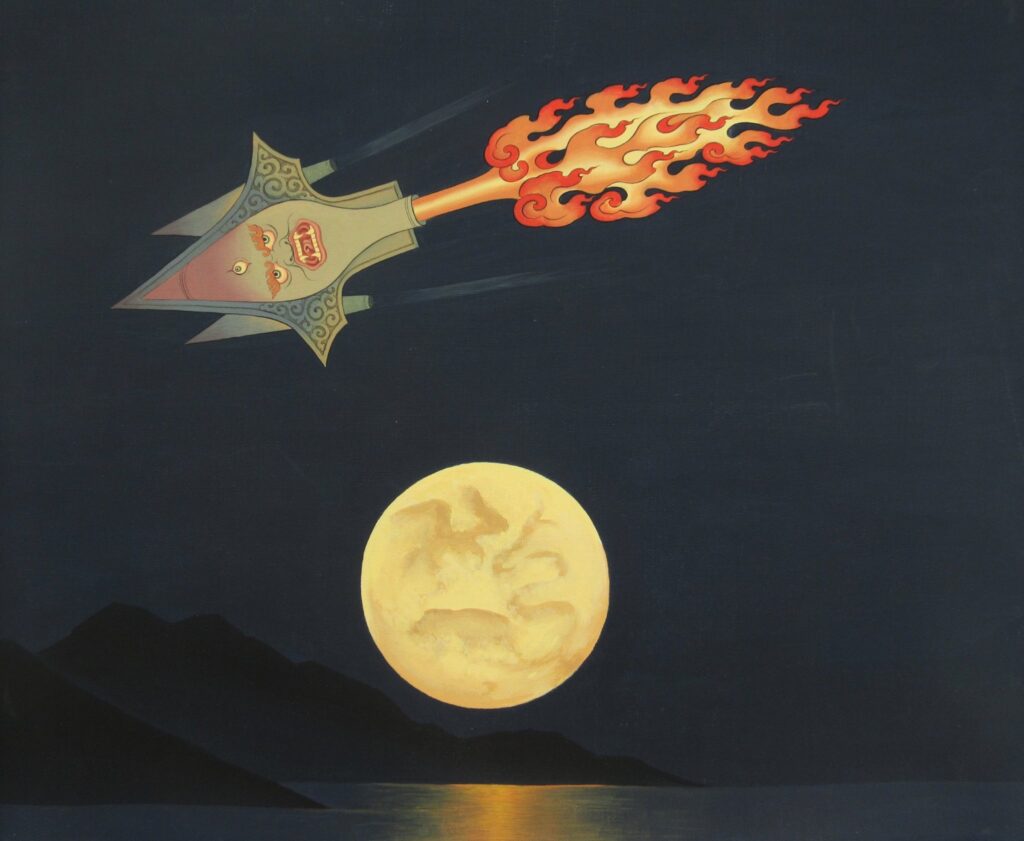

A few of them are quite unique and their meaning is lost on me—fodder for future questions to Karma and Sonam.

Dolpo in spring. This is very much how I remember Tibet:

There is a painting here in the hotel of a person standing at Lake Phoksindu, out on a small point of land in the water. In the sky, a dark grey cloud looks like a dragon. There are a few yaks in the lower right hand corer, kicking up their feet and running. Two birds are flying in the sky.

I asked Karma, “What do you think your father was thinking of when he painted this?”

He said, “Well, that cloud is thunder, and I think the person is just standing there, enjoying the thunder. The yaks are startled by it because they don’t know what it is—only that is a a powerful noise, which could indicate some danger, so they are frightened and are running away.”

A whole moment of Dolpo life captured in a snapshot.

This is why I come to Nepal. I am not as much interested in sightseeing as I am in seeing into the stories and lives of ordinary people. I would rather follow one good story like this over a few years, in multiple conversations with multiple people than I would visit the great ‘modern wonders’ of the world.

I also enjoy giving a listening ear to those whose voices have not really been heard. Especially to young people who can come to value their own culture and past by telling the stories they have lived. I appreciate their openness and their generosity in sharing these stories and the beautiful details of their lives, which are slipping away moment by moment. I also enjoy hearing about how they are navigating the rapid changes that are happening to them as electricity and roads and so-called ‘improvements’ reach their homeland.

I wish you were here.

Lekshe

November 20, 2023